I learned to dive to do research on the sea otter vs abalone conflict. Those simple words evoke strong memories. I was the only female in the NAUI dive class, and the instructor was a Navy seal who delighted in challenging (picking on) me. I was a relatively good swimmer and could float easily, but that required more weight to keep me submerged (my classmates nicknamed me “bubble-butt.”) Breathing underwater with a regulator attached to an air tank was an important skill that didn’t come easily, especially the exhale part, which was essential during our first field trial when we were required to drop our regulators and make a free ascent from 30 feet. I forgot to breathe through my nose on my way up and gave myself a royal mask squeeze and two black eyes. But I managed to get certified after our 5-week course, which included my first open ocean dive off Cannery Row in Monterey — my firsthand view of an underwater garden: kelp beds, iridescent marine life (but no abalone). That first open-ocean underwater experience motivated me to invest in a Nikonos underwater camera and lighting system so I could photograph marine life in their natural environment. I taught myself how to use it.

“Now I know why you dive,” I exclaimed to ab diver Jim Finch when I met him in Santa Barbara harbor on my first trip to Southern California. “It’s beautiful underwater!!” Jimmy looked at me and chuckled, shaking his head. “We dive to make money,” he replied.

True, commercial abalone diving was a business, and one where a diver needed persistence more than formal education to make a living, although many did have college educations but chose to dive for the freedom, the self-reliance, the chance to earn good money. Many ab divers also were [are] surfers and possessed uncommon knowledge of ocean cycles. They relished days when the swell was too big to go to work diving; they went surfing instead. And many divers, like Jim Finch and Rudy Mangue (and my husband Bruce) were keen observers with photographic memories. When Jimmy and Rudy moved to Santa Barbara because sea otters had overtaken the abalone turf on the central coast, they knew the bottom was different at the Channel Islands.

Ocean conditions – the currents, the gyre – are different south of Point Conception. When ab divers began picking abalone in Southern California and the Channel Islands, abalone reefs were cobbled with red abalone, as well as pinks, greens, blacks and whites (smaller abalone species). Gunwale-sagging loads of abalone flooded the market during that time of abundance, and abalone processors set up shop in Santa Barbara to handle the influx of virgin stocks that had built up after the fur trade had eliminated sea otters in Southern California. But old-time divers knew from the beginning that picking abalone in many spots in the Channel Islands was a one-time proposition because those areas were not producing young abalone.

The popularity of sport diving in Southern California mushroomed along with the decline in abalone. The sport size limit for reds was 7 inches, while the commercial limit was 7 ¾ inches – a fact that rankled commercial divers who began lobbying for a change in abalone management. Around the same time, abalone hatcheries began growing abalone in concrete raceways on land or in barrels suspended in the ocean. These aquaculture enterprises began with native abalone and induced them to spawn and grow on artificial substrate. Abalone are typically slow growing, averaging about one inch per year. Aquaculture farms like the Ab Lab in Port Hueneme, Southern California, and the Abalone Farm in Cayucos, began marketing 2-to-3 inch “cocktail size” abalone to upscale restaurants. And they began selling baby abalone.

Rudy Mangue was president of the California Abalone Association, representing commercial ab divers; Jim Finch was treasurer. The CAA hatched a plan to lease specific reefs and reseed productive abalone turf where the abalone had been picked out. But first they had to secure permission from the Department of Fish and Game and Fish and Game Commission. The concept was that commercial divers would invest their time and money to plant abalone in designated bottom lease sites, with the guarantee that they could harvest a percentage of the crop at 5-inch size rather than the commercial size of 7 ¾ inches. After numerous meetings and negotiations, the Commission agreed with the plan, on the condition that a Department of Fish and Game biologist survey each bottom lease site first, to ensure that it was devoid of abalone before divers planted the baby abs.

I went out with Jimmy and Rudy on the day they prospected for the coordinates of the bottom lease reef on the backside of Santa Rosa Island that Rudy remembered from years past, that had once been productive. Jimmy was ‘live boating,” following Rudy’s bubble trail with the boat while Rudy canvassed the area underwater. That’s when Rudy encountered a white shark. As I wrote in Abalone Divers, a Vanishing Breed? the shark attacked from below. Rudy smacked it on the nose with his ab bar and sprinted to safety on deck. He admitted later that live-boating had surely saved his hide — maybe his life.

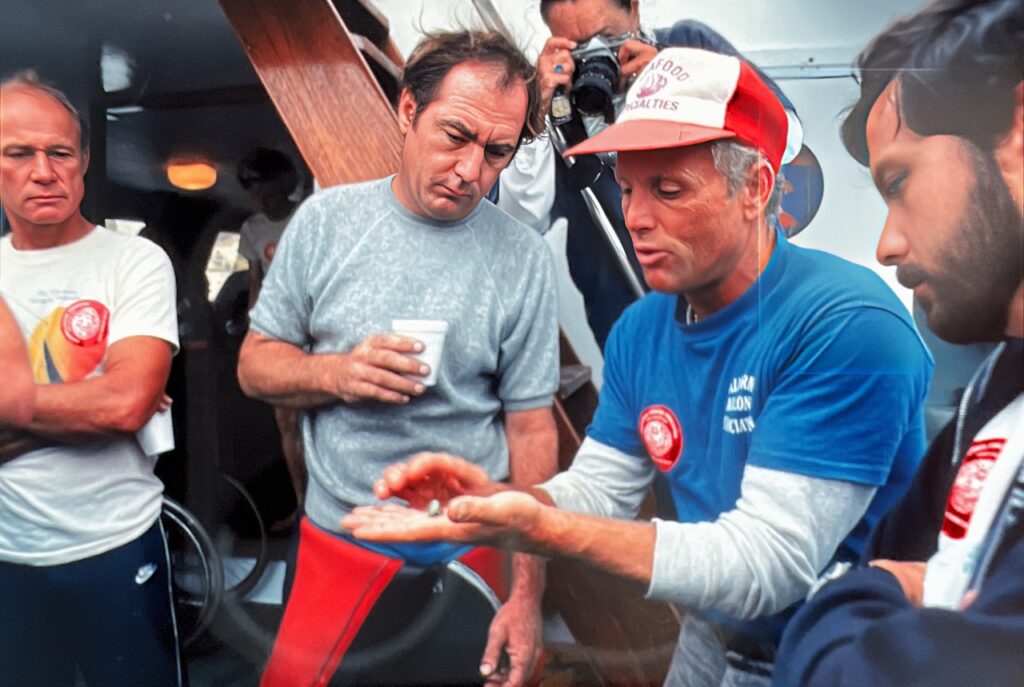

Rudy Mangue showed ab divers how he punched the white shark and escaped

After the shark scare, Rudy and Jimmy moved up the line and found another good site a few miles away to lease. Ultimately, CAA leased several reefs to restock with baby abalone. They bought the seed from the Ab Lab for $0.50 to $1 apiece and stored the yearling abalone in barrels in Santa Barbara harbor until they were ready to plant them out.

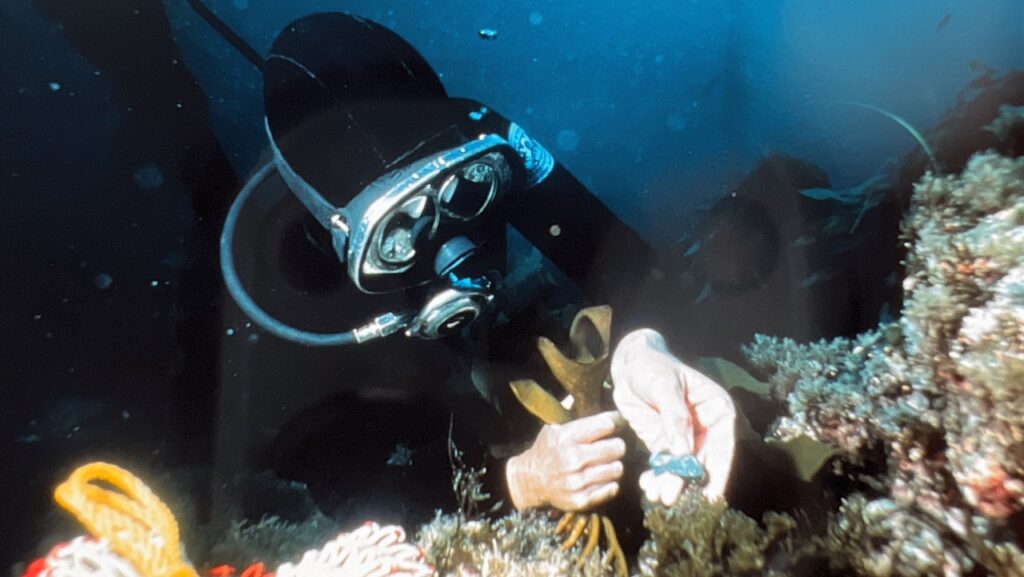

Ab diver Win Swint and other divers survey a bottom lease site off Santa Cruz Island in a 15-foot swell.

The most ambitious venture that CAA brainstormed was the Great Abalone Plants, the first joint commercial-sport effort to restore California’s declining abalone resource.

Long hoping for sport participation to boost their reseeding workforce and defray the cost of seed abalone, CAA enlisted the help of sport divers at $100 a head; they used the money to purchase baby abalone. Santa Barbara’s sport charter company donated the Conception, the crown jewel of Santa Barbara’s sport dive fleet, to carry sport divers to the bottom lease site at San Miguel Island for the First Great Abalone Plant in the summer of 1983.

The Conception’s galley buzzed with anticipation the night before the plant as commercial divers shared their experiences along with a film that gave a crash course on reseeding procedure. Divers should relocate predators like starfish and distract reef fish by cracking a sea urchin, then scrape the invertebrate turf off the planting site – narrow, smooth-faced crevices undercut in the reef near sandy bottom and other abalone. They should place a few little snails in the clearing, pressing the shells gently until the abalone clamped down. The clusters should be spaced at least two feet apart to avoid predation. On film the job looked easy: in reality, it wasn’t. (I highlighted the challenges in my story The Great Abalone Plant.)

Most of the sport divers there said they had never seen live yearling abalone, although all had picked and eaten legal size adults. The camaraderie generated between sport and commercial divers was a rewarding side benefit, as about 30 sport divers, armed with good will and zip-lock baggies of baby red abalone, joined at least 8 other commercial abalone boats in the reseeding effort. Sport divers learned in a hurry that hand-seeding baby abalone is painstaking, time consuming, exhausting – yet exhilarating. At day’s end, divers had planted 7,000 baby abalone. Brimming with new appreciation of the resource and each other, they were already planning the Second Great Abalone Plant.

The Second Great Abalone Plant took place at Catalina Island about a year later. Commercial ab divers Mary Stein and Randy Brannock coordinated this effort, enlisting sport divers to reseed green abalone at a bottom site in Lovers Cove. Again, the camaraderie between commercial and sport divers was palpable, and the cooperation was much appreciated by everyone.

Mary Stein greeted sport divers participating in 2nd Great Abalone Plant at Catalina Island

Mary Stein handed a baggie of baby green abalone to sport divers to plant at Catalina Island

The success of these abalone reseeding efforts was never officially documented, although ab divers reported seeing increases in abalone populations at San Miguel Island and other places.

But overall, abalone continued to decline, especially green, pink, black and white abalone – white and black abalone made the endangered species list.

Beginning around 1985, red abalone began appearing with grotesque, shrunken foot muscles. The disease is called Withering Syndrome (WS), the cause is attributed to an intracellular bacterium. All seven abalone species are susceptible; the degree varies between species and with water temperature. WS severely impacted wild abalone in Southern California. Both the sport and commercial fishery for red abalone closed by 1997 (the black abalone fishery closed in 1993). Although overfishing was also implicated, scientists attributed the main cause of the decline to WS (not sea otters).

In recent years divers have reported a red abalone bloom at San Miguel Island. And there’s renewed talk about the possibility of reopening a fishery in Southern California. But the sea otters translocated to San Nicolas Island also are increasing in number, and San Miguel Island is only a one-day otter swim away. So there’s no end in sight for the abalone vs. sea otter conflict.

PHOTOS AND CAPTIONS

Sport and commercial divers congregated at San Miguel Island for the First Great Abalone Plant

Jim Finch instructed sport divers how to handle baby abalone

Handful of baby red abalone

Baby red abalone underwater

Mary Stein planted baby green abalone on reef at Catalina Island

John McMullen grew abalone at the Ab Lab in Port Hueneme CA

Baby abalone in 55-gallon grow out barrels at the Ab Lab

The Abalone Farm in Cayucos, on the central coast, grew abalone in concrete raceways, pumping seawater up the cliff to fill the grow-out pens